“How hard to read, O Soul,

The riddle of life here and life beyond !

As hard as in the pearl to pierce a hole

Without the needle-point of diamond.

day.”

~ Princess Zebun-Nisa

We often hear of her aunts the famous Princess Jahanara and Princess Roshanara, sometimes of her sister Princess Zeenat-un-Nisa because of the famous mosque in Delhi made by her but not much is known about Princess Zebun-Nisa who true to her penname Makhfi has been concealed from the public eye.

She was the eldest daughter of Emperor Aurangzeb and his wife Dilras Bano, born in Daulatabad on 5th February 1638. Dilrus Banu Begum, was the daughter of ShahNawaz Khan a high ranking Mughal officer descended from the Safavis of Persia.

Her siblings from her mother were Zeenat-un-Nisa, Zubdat-un-Nisa, Mohammed Azam, Mohammed Akbar.

ZebunNisa came from a family skilled not only in battle but with considerable literary talent as well. Babar displayed freshness in his memoirs, as did his daughter GulBadan Begum, biographer of Emperor Humayun, Jahangir and JahanAra Begum. Whether Akbar, Jahangir, Shahjahan or even Aurangzeb they all displayed a keen intellect and literary taste.

As was usual in those days she committed the Quran to memory under the guidance of Hafiza Mariam and was rewarded 30,000 gold-pieces by her delighted father.

A lady named Miyabai was appointed her tutor, and she learned Arabic mathematics and astronomy and sciences from her and other teachers.

Many poets sought her patronage and she employed many scholars on liberal salaries, who produced literary works at her bidding or copied manuscripts for her. This was a boon to them as Aurangzeb did not encourage or patronize poets and non-religious scholars.

She employed skilled calligraphers to copy rare and valuable books for her and, as Kashmir paper and Kashmir scribes were famous for their excellence, she had a ‘scriptorium’ also in that province, where work went on constantly. She personally supervised the work and went over the copies that had been made on the previous day.

Mulla Safiuddin Ardbeli translated the Arabic Great Commentary under the title of Zeb-ut-tafsir under her patronage, though it is rumoured that it was the Princess herself who was the real author of the commentary.

Despite the strict religion followed by her father, Aurangzeb, like her aunt Jahan Ara and uncle Dara Shukoh, Zebun-Nisa was a Sufi in her inclinations and her poetry bears it out. In fact she was a great favourite with her uncle Dara Shukoh and she modestly attributed her verses to him when first she began to write, and many of the ghazals in the Diwan of Dara Shukoh are said to be by her.

LIFE passes by, a caravan of shadows,

Leaving no track or voice upon its way;

Only the torch of beauty, where it flashes,

Spreads in the world disaster and dismay.

She helped her father in affairs of the court too but was always veiled when not in the women’s quarters.

She started writing Persian verses under the pen- name of Makhfi or the Concealed One.

This was a popular pseudonym and was used by many other royal ladies. However, the Deewan e Makhfi from which I will quote her poems (translated from Persian by Magan Lal and Jessie Duncan Westbrook is attributed to her and widely recognized as her work.

Zebun-Nisa’s verses testify to her skill as a poet.

Not much is known about her life as she had earned the displeasure of her stern father and no court chronicler dared to speak of her. According to the editors of Deewan e Makhfi from her early youth she wrote verses, at first in Arabic ; but when an Arabian scholar saw her work he said : “Whoever has written this poem is Indian. The verses are clever and wise, but the idiom is Indian, although it is a miracle for a foreigner to know Arabian so well.” This piqued her desire for perfection, and thereafter she wrote in Persian, her mother tongue.

She had as tutor a scholar called Shah Rustum Ghazi, who encouraged and directed her literary tastes.

On the request of Shah Rustam Ghazi, Aurungzeb who himself cared little for poetry made an exception in favour of Zebun-Nisa andinvited poets to his court.

Some of the poets whom she interacted with were Nasir Ali, Sayab, Shams Waliullah, Brahmin, and Behraaz and Nasir Ali.

This group of poets would match each other in skill and often have a ‘tarahi’ competition where each poet completed a given line within the same metre in his/her own way. Zebun-Nisa excelled in tarahi muqabala.

Mushairas or poetic soirees would be held .

Though it is often said that Mughal princesses were not allowed to wed, its not true. The stricture was that the groom had to be from within the family or another suitable royal family. Her sister Mehrun-Nisa was married to her first cousin Izid Bakhsh,a son of Murad Bakhsh.

Zebun-Nisa too was betrothed as per the wish of Shah Jahan, to Suleiman Shikoh, son of Dara Shikoh. This might have been a very compatible match but Aurangzeb who had no time for the more popular Dara is said to have had the young prince poisoned.

In a very Indian tradition, she had her own variation of the swaymvara arranged to meet and test the attainments of the many suitors for her hands.

One of those who wished to marry her was Mirza Farukh, son of Shah Abbas II of Iran ; she wrote to him to come to Delhi so that she might see what he was like.

Marrying the daughter of the Mughal Emperor was a matter of pride and Mirza Farukh came with a magnificent retinue. She held a feast for him in her garden but herself appeared with a veil on her face.

The young Prince offended her sensibilities by asking for a sweetmeat in a play of words which meant a kiss.

“Ask for what you want from our kitchen,” was her response.

She refused to marry him informing her father that despite his rank and royal descent his manners did not find favour with her.

Her personal life was not destined for happiness and she could not find true love or a companion. Sulaiman Shikoh was poisoned and Mirza Farukh she found discourteous and too forward.

Her pen name Makhfi also bears testimony to her Sufi leanings as it could be that only after death and in union with the true Beloved, God would she disclose her face.

Once Nasir Ali asked her to unveil with the verse:

“0 envy of the moon, lift up thy veil

and let me enjoy the wonder of thy beauty.”

She answered :

“I will not lift my veil,

For, if I did, who knows ?

The bulbul might forget the rose,

The Brahman worshipper

Adoring Lakshmi’s grace

Might turn, forsaking her,

To see my face”

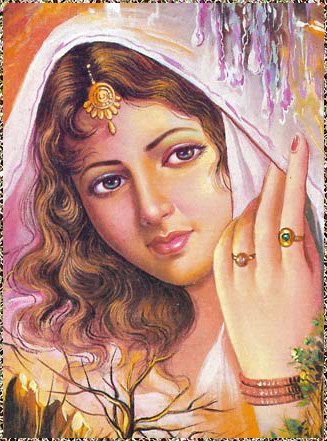

In personal appearance she is described as being tall and slim, her face round and fair in colour, with two moles, or beauty-spots, on her left cheek. Her eyes and abundant hair were very black, and she had thin lips and small teeth. In Lahore Museum is a contemporary portrait, which corresponds to this description. She dressed simply and in later life she always wore white, and her only ornament was a string of pearls round her neck.

A modification of the Turkish dress is attributed to her: the angiya kurti which suited the Indian conditions.

Distrust between father and daughter meant that the last 20 years of her life were spent imprisoned in the fortress of Salimgarh,. There are various reasons given for it, including her friendship with her brother, Prince Akbar, who had revolted against him. The Deewan e Makhfi even suggests it was because of her sympathy with the Mahratta chieftain Shivaji.

There she spent long years, and there she wrote much bitter poetry :

So long these fetters cling to my feet !

My friends have become enemies,

My relations are strangers to me.

What more have I to do with being anxious

To keep my name undishonoured

When friends seek to disgrace me ?

Seek not relief from the prison of grief,

Makhfi ; thy release is not politic.

Makhfi, no hope of release hast thou

Until the Day of Judgment come.

Even from the grave of Majnun the voice comes to my ears

” Leila, there is no rest for the victim of love even in the grave.”

She died in 1702 and was buried in Delhi in the garden of ‘Thirty Thousand Trees’, outside the Kabuli gate. Her tomb was razed to the ground when the British laid the railway lines. It is said her mortal remains were shifted to Sikandra in Agra

References: Translations of the verses from the Persian are taken from Deewan-e-Makhfi translated by Magan Lal and Jessie Duncan Westbrook & Zeb-un-nissa; Tr. by Paul Whalley (1913). The Tears of Zebunnisa: Being Excerpts from ‘The Divan-I Makhf’

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of NEWSD and NEWSD does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.