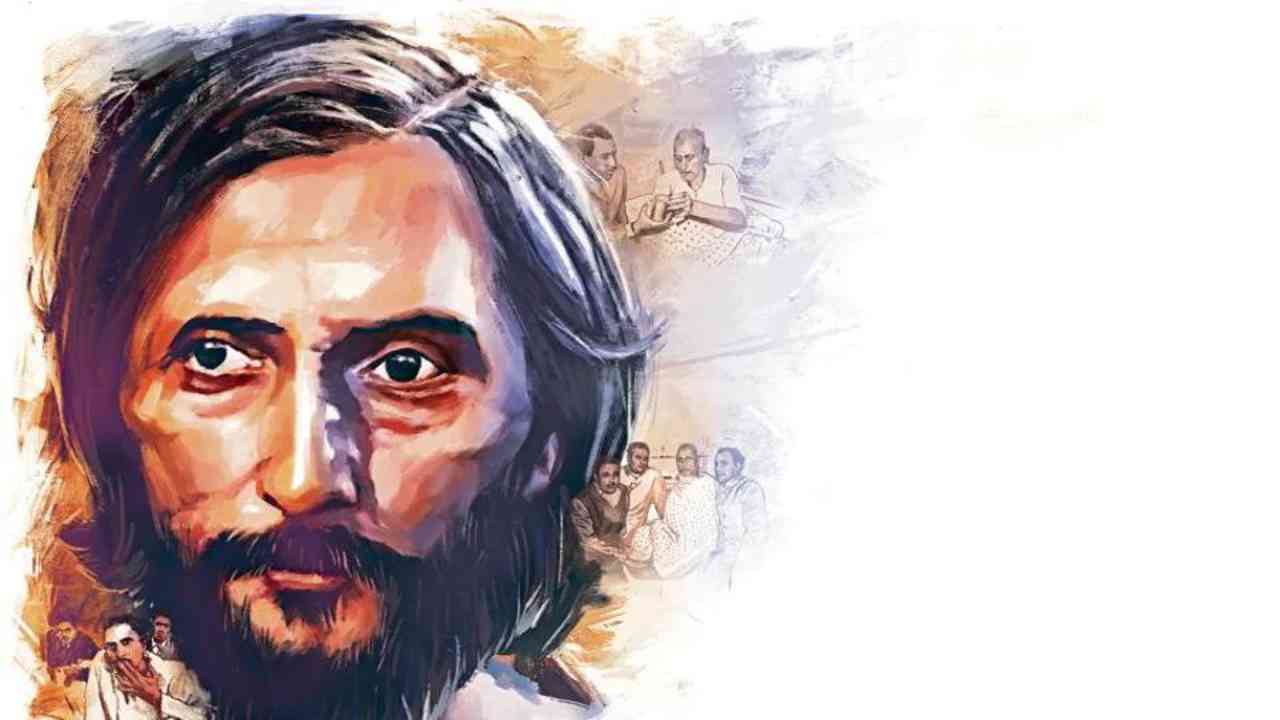

In his essay Nehru and Nirala, historian Ramachandra Guha recalls an anecdote he had heard from anthropologist Triloki Nath Pandey.

The then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru had just returned from a visit to China. He was addressing a public meeting in Allahabad, where revered Hindi poet Suryakant Tripathi ‘Nirala’ then lived. Nehru accepted a few garlands from fans in the crowd and said, “I have come from China and heard there a story of a great king who had two sons. One was wise, the other stupid. When the boys reached adulthood, the king told the stupid one that he could have his throne, for he was fit only to be a ruler. But the wise one, he said, was destined for far greater things — he would be a poet”. With these words, Nehru took the garland off his head and placed it as an offering at Nirala’s feet.

Suryakant Tripathi ‘Nirala’ was poet, novelist, essayist and pioneer of the Chhayavaad (Neo-Romantic) movement of Hindi literature. Like his pen name Nirala (unique), his craft was also unique. From comic novel Nirupama to heartbreaking novella Kulli Bhat, he experimented with different genres and themes. The language of his poem was never defined.

Renowned Dhrupad maestro Umakant Gundecha tells ThePrint, “He wrote in both free verse and traditional metres but despite no fixed format, he never failed to mesmerise the reader.”

Sati Khanna, one of Nirala’s translators to English, once said, “He will last not because some academy recognises him and shows him respect but because those who get to read him become drunk on his poetry.”

On the poet’s death anniversary, let’s revisit his life and works that gave a new direction to Hindi poetry and literature.

A life full of struggle:

Nirala was born on 21 February 1896 as Suraj Kumar Tevari in Midnapur district in Bengal. His primary education was in Bangla.

“To review Nirala’s life is to confront a series of catastrophes, failures and losses that begins with the death of his mother when he was two years-old,” American novelist and translator David Rubin writes in Nirala and The Renaissance of Hindi Poetry published in 1971.

He was banished from his father’s house for failing his matriculation exams when he was only 15. Within three years, he lost his father, wife, brother and sister-in-law to an influenza epidemic. Faced with an uncertain existence, he started taking up jobs of proofreading and copy-editing to earn some money, but wrote alongside. His first poetry collection, Anamika, was published in 1923.

In the preface of his poetry collection Parimal, he wrote, “Like humans long for freedom, poetry also wants to be free. The way humans seek to get rid of the bondage of karma, the poem seeks to break away from the rule of verses.”

Nirala went on to become the leading figure and pillar of the era of ‘mukt-chhand’ (free verse) poetry in Hindi.

Nirala’s daughter Saroj passed away when she was just 18, an event that shattered him to the core. He went on to write Saroj Smriti, which according to David Rubin, marked his full maturing as a poet.

“Chhor kar pita ko prithvi par,

tu gayi swarg, kya yah vichaar

“jab pita karenge maarg paar

yah, aksham ati, tab main saksham

taarungi kar dustar tam”

“Did you leave for heaven and left your father behind on earth, thinking that when father arrives at his appointed hour of death, ignorant, and inefficient, to cross the river of intense darkness, I, as his efficient and worthy daughter, shall hold his hands?” as translated by author Anumita Sharma.

Nirala and music:

“There is a deep resonance between Nirala’s poems and music. Nirala was very well aware of how the laya-taal works,” says Gundecha. “We came across his poems and thought of composing him. The preface of the poem that we chose to compose already had a mention of how he had written it in Dhrupad’s bol-baant style (an ancient form of Indian classical music). He also wrote which taal and raga he had used in his poems. There were times when he used to sit at the harmonium during poets’ gatherings to recite his poems. Only someone who knows about the nuances of Indian classical forms — Khayal, Dhrupad, taal, laya — can do that.”

Nirala is one of those rare poets whose poetry, composed in different ragas, is still being performed. He was a devotee of Saraswati, the Goddess of music and wisdom, and no other poet has written as many poems on Saraswati in Khadi Boli in Hindi as Nirala has.

A mirror to society:

At a literature festival held in Indore in 1936, Mahatma Gandhi asked, “Where is Hindi’s Tagore?” Nirala took offence and pushed everyone aside in the gathering to walk ahead and ask Gandhi if he had read enough Hindi literature. After Gandhi confessed that he had not, Nirala said he would send him his and Tagore’s work.

Nirala’s ego and arrogance were well known. He struggled throughout his life to earn money, yet later, when he was recognised as one of the greatest poets and the government offered him money to sustain himself, he refused. His friend and fellow poet Mahadevi Verma took the responsibility and was granted some money to take care of him. Nirala died in 1961, in dire financial straits, with no family and suffering from schizophrenia.

His poems gave voice to the voiceless, exposed the hypocrisy of the society while resonating with the reader. His poem Wah Todti Patthar, creates a heart-wrenching picture of a woman stone crusher.

“Wah todti patthar

Dekha maine Allahabad ke path par

Wah todti patthar

Chadh rahi thi dhoop

Garmiyon ke din

Diva ka tamtamata roop

Uthi jhulsaati hui loo

Rui jyon jalti hui bhoo

Gard chinagi chha gayi”

Beside a road in Allahabad,

I saw her breaking stones.

The sun climbed the sky.

The height of summer.

Blinding heat, and the loo blowing hard,

Scorching everything in its path.

The earth under the feet

Like burning cotton wool,

The air filled with dust and sparks.

It was almost noon,

And she was still breaking stones.”

In another poem titled Bhikshuk, the realistic symbolism stuns the reader.

“Pet-peeth dono milkar hain ek,

Chal raha lakutiya tek

Mutthi bhar daane ko – bhookh mitane ko

Munh gati purani jholi ka failata –

Do took kaleje ke karta, pachatata, path par aata”

“He comes.

Making us repentant with remorseful remarks,

He comes on path.

His stomach and back seems one,

A stick in hand,

Asking for alms and grain,

To satisfy his hunger.

He spreads forward

His torn satchel,

Making us repentant with remorseful remarks,

He comes on path.”