Being the city of Nawabs and ‘cultural centre’ of Northern India, Lucknow remained a good patron of literary activities. With political crises at Delhi, poets bereft of patronage left for Lucknow which provided them with some option and most of them permanently migrated. Mir Taqi Mir (d.1810) and Mirza Muhammad Rafi ‘Sauda’ (d.1781) are the best examples. Sauda came to Lucknow in 1770 and lived there till his death in 1781; Mir was invited by a Nawab in 1775 and remained there throughout his life till 1810, though always pinning for Delhi. The city warmly welcomed them and their new literary innovations which influenced the traditional writing skills. This is true for the printing technology as well.

The introduction of print in Lucknow goes back to the time of Nawab Ghᾱziuddin Haider (r.1814-27) who is said to have founded Lucknow’s first typographic press, Matbᾱ’e Sultani or Royal press in AD.1817. The press was much engaged in the production of scholarly and religious works. Some of the major works includes Haft Qulzum or ‘Seven Sea’ which was a Persian dictionary & grammar in seven volumes compiled by Qabul Mohammad (a courtier) in 1820-22 and Tᾱj al lughᾱt, a dictionary of Arabic into Persian.

But the real development of the print culture in Lucknow starts from 1830 with the introduction of lithography by Henry Archer (superintendent of the Asiatic lithographic press at Kanpur) on the insistence of King Nᾱsiruddin Haider (r. 1827-37). In 1831 he published the first lithographed book from Lucknow ‘al bahjah al Mardiya which was an Arabic commentary by the famous Quranic commentator, Abu al-Fadl ‘Abd al-Rahman b. Abi Bakr b. Muhammad Jalal al-Din al-Khudayri al-Suyuti, also known as Ibn al-Kutub (son of books).

For a sufficient time, the printing and publishing industry enjoyed the royal patronage. Gradually the technology shifted into the individual hands or local elites, especially to Muslim Ashrᾱf and business class. The pioneer in the field was Maulavi Mohammad Husain (an Islamic scholar generally known by the name of Haji Harmain Sharifain) who set up the Mohammadi press in 1837 and gathered few expert calligraphers. In 1839 Mustafa khan (a rich glass merchant) established the second press called Mustafᾱi Press which gradually legged behind others in the entire subcontinent with its great artistic excellence and commercial experiences. The period of 1840’s saw the emergence of few more presses. This includes Jalali (1840), Alavi Press (1841), Afzal ul Mutabe’ (1843), Mir Hasan Press (1844), Mohammadi Press (1845) Maula’i (1845), Husaini, Khayali, Sangin, Syed Mir Hasan, Mohammadia (1846), Mohammadi wa Ahmadi (1847), Murtazavi (1849), Mehdiᾱ (1849) etc

But, the year of 1849 came as a big blow for the print industry because Wajid Ali Shah (r. 1843-56) ordered all the presses in the city (including the Royal press) to be closed. This has badly affected the local printers forcing them to move somewhere else. Thus, Maulavi Mohammad Husain and Haji Mustafa Khan had to leave Lucknow and re-establish themselves at Kanpur. Few months later, the ban on press was removed but with few restrictions. Resultantly, all the printing houses were to work under royal control and must bear the seal of Matba’e Sultani. This strict censorship acted as barrier to the evolution and progress of Journalism in Lucknow which came to fore only from 1856 i.e. the period of annexation of Awadh and thus all the newspapers from Lucknow began late, from the year 1856 or 1857 except for Lucknow Aḵhbᾱr which had appeared in 1847.

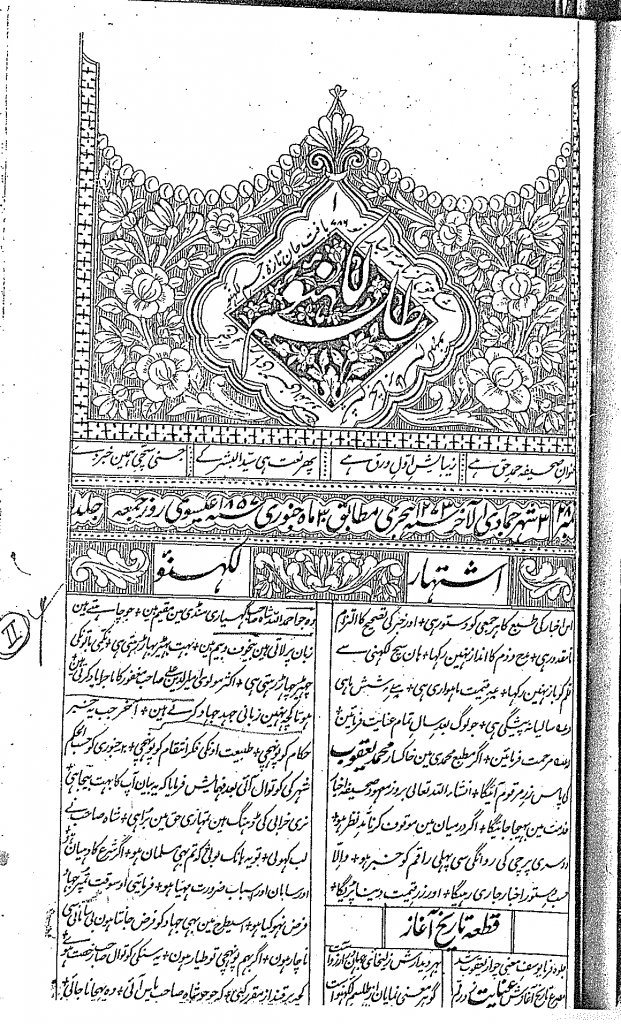

The two most influential newspapers of Lucnow were Sahr e Sᾱmri and Tilism e Lucknow providing details of contemporary life in fairly critical tone. Here, Tilism-e Lucknow is the most commonly talked about not only because of its outer beautiful look which perfectly corresponds to the culture of Lucknow but also because of its content that reflects a true picture of the society of that time. It was printed at Matba’e Mohammadi by its editor and owner Maulavi Mohammad Yaqub Ansari, a close friend of the author Rajab Ali Beg ‘Suroor’ and a member of the family of Firangi Mahal. The people of Firangi mahal had always been of greater intellectual capacity, concerned for the problems of society and culture and so was the Maulavi Yaqub. Instigating hopes among the people of Lucknow for restoration of old regime and reflecting the local reluctance to accept the new English rule must have led him to publish a newspaper. The paper however ceased publication due to the upheaval of 1857 and re-started later under a different name Matba’e Karnamah Akhbar.

The title page of Tilism was beautifully decorated with floral patterns, the name of the newspaper Tilism e Lucknow was boldly written in the middle and around the name following verse was printed:

Shukr e Haq kuz Na’mey Akhbar e nu O new paper of news, be thankful to God

Yaft Jaan e taazeh jism e Lucknow He has filled a new life into Lucknow

Ganj gohar haye’ maaney andarust It has a hoard of jewels of meaning

Chishm baksha bar Tilissm e Lucknow Open your eyes on the magic of Lucknow

Two verses were added to these lines from the issue of 26 September, No. 10, which were to praise Allah and Prophet:

‘Unwan e Sahifey hamd e Haq he At the top of the page is a hymn to God

Zeba’ish awwal e warq he it is the beauty of the first page

Phir na’at he sayyad ul basher ki this follows with praise of Leader of men

Jis ne sacchi hamey khabar di who has informed us true gospel

This was followed by the number of the issue, date in Hijri and Christian Calendars, the day and the volume number. The rest of the page was divided into two columns- first contains the advertisement followed by, from the issue of 17th October, a chronogram which got change after few issues; the second column hold the local news. The newspaper acts a mirror to present the contemporary local political, social, cultural and economic life. It truly narrated the aftermaths of the Annexation and the plight of the people.

The newspaper provided us with important data on the impact of annexation on the various sections of society of Lucknow- the artisans, production of the handicraft, migration of the weavers in large numbers, prices of essential commodities, large scale unemployment, and a picture of disillusionment, and despondency from all the sections of the society. It also brings to the notice the impact of Summary Settlement, which curtailed the powers of the chieftains and big talluqadars in a considerable manner. The acts of highway robbery, the capture of nawabi buildings, the destruction of the old settlements and the dislocation in the name of beautification of the city have all been described. Hence, the rural elites, mainly on the coast line, were gathered and getting organized to resist the Colonial authority.

This paper also provides first hand reports of the process of mobilization undertaken by famous rebel leader Maualvi Ahmadullah Shah, especially in the background of Hanumangrahi episode of November 1855, where Maulavi Amir Ali and his supporters died while fighting with the forces of Awadh Government and the English forces. It also provides the minute details such as Maulavi Amir Ali became a ‘cult figure’ and a ‘halo’ was created around him, the ‘charisma of the martyr’ grew so much that his death anniversary was celebrated in a befitting manner. The editor has no opportunity to use the hyperbolic language but on occasions, he also undertakes sermonising gestures. Since the last available issue of this weekly is on 8th May 1857, so we are not sure how he would have reported the event of 1857.

But the event of 1857 came as a big blow to the process of journalism and all the efforts of local newspapers were put to an abrupt end. Only few of the printer-publishers could manage to re-start after the event. The Asafi Press of Beni Prasad, the Alavi Press of Ali Bakhsh Khan, the Gulshan e Mohammadi Press of Masahib Ali and the Samar e Hind Press of Pandit Baijnath. Maulavi Ya’qub issued another journal called kᾱrnᾱmᾱh. The Munshi Naval Kishore Press could even manage to get license and use the opportunity to lead the print industry in Lucknow.

The English press at Calcutta was highly critical of the tone and reporting of the events adopted by these indigenous newspapers. Such English language newspapers kept on pushing the Colonial administrators to stop their publications, confiscate their printing presses and cancel the registrations as the indigenous were inciting the masses to rise against the Government. In fact there emerged a host of Acts limiting and controlling the reach of local newspapers. The first among them was the Gagging Act of 13th June1857 which empowered the government to prohibit the publication or dissemination of any newspaper, book or other printed material which could cause a threat to government.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of NEWSD and NEWSD does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.